In 1906 Australia released The Story of the Kelly Gang. Not only was it Australia’s first film, but it was also the first feature film in the world. Australia was seen as a pioneer for the film industry suggesting that the future of Australian film would be rich, vibrant, successful and continue to be groundbreaking. But what followed throughout the next century would divide the nation and beg the question; should we fund films for the sake of art, or should they be funded only if there is a guarantee in the return of revenue?

While many Australian films have been ‘successful’, it seems that overall, the Australian Film Industry, and it’s funding, in the last four or so decades have been turbulent and controversial.

In the 1970s there was a revival in the screen industry. Prime Ministers John Gorton and Gough Whitlam set off this renaissance period by creating several government funding programs such as the Experimental Film Fund, the Australian Film, Television and Radio School (AFTRS) and the Australian Film Development Corporation (AFDC). It is Gough Whitlam that is truely credited with this resurgence period. Under his government, the AFDC became the Australian Film Commission (AFC). The AFC, unlike the AFDC, prioritised funding for cultural relevance and artistic excellence over the expectation of economic success.

During this period (1970-1985) the era of Ozploitation arose and 10BA tax incentives were introduced.

Ozploitation is categorised as a low budget film with the only requirement being that it’s an Australian genre film that exploits Australian stereotypes.

Access to funding and tax incentives like 10BA, which “allowed investors to claim a 150 percent tax concession and to pay tax on only half of any income earned from the investment”, gave way to the creation of nearly 400 films creating a ‘boom’ period for the industry.

In the late 80s and early 90s, the 10BA tax laws were cut back due to the tax evasion scandals that came out of it, as well as the increasing cost of the tax incentive.

This was also the era for internationalisation which came in the form of co-productions, financing, set locations, and even cast and crew, raising the question of what classifies as an Australian film?

National identity has played a significant role throughout Australia’s filmography. It is through the formation and portrayal of this national identity that the industry has both helped and hindered Australian content internationally and domestically.

Growing up in America my experience with Australian film was extremely limited and like most people living outside of Australia Crocodile Dundee was just about the extent of it. That mixed in with the iconic red dessert, thick accents, remote outback stations, very little diversity and maybe some didgeridoo sound effects. But this doesn’t adequately represent the diverse nation so when the internationalisation era came in the 90s and we began to see more diversity in LGBT+ communities, multiculturalism, urban settings and so on it seemed like a step in the right direction and in a sense it was. Many films in this era were deemed successful at the box office domestically and abroad but the industry still seemed to be failing in terms of capital.

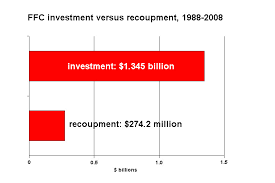

The Australian Film Finance Corporation (FFC), had a big problem on their hands. They were funding films at a much higher rate than they were getting back and thus it would only last until 2008 when it, along with the AFC and Film Australia merged into one entity; Screen Australia.

In 2014/2015 Screen Australia funded over 3 billion dollars in the industry which also allowed for the creation of 25,000 jobs however in recent years it has, and likely will continue to have its budget reduced. In 2017/2018 Screen Australia had its budget reduced by 3%, nearly 2.6 million dollars which will have a big impact on the future of Australian films.

These budget cuts to the arts reveal that the government is prioritising revenue back over the cultural necessity of making Australian films, even though a majority of the public believe the government should fund the arts regardless.

The perceived ‘failure’ of the screen industry doesn’t just come from the debate around funding or the idea of Australian identity, but in large part, it can be attributed to market failure.

Australian films are being failed at the distribution level and have had an exceedingly difficult time getting cinemas to exhibit their work. Furthermore, they have had to compete with Hollywood for screen time, an industry that has proven time and time again to get butts in seats and generate revenue for cinema owners.

As outlined above several things must change in order for Australian content to succeed. In general the idea of what qualifies a film as Australian needs to be reexamined. A few of the more successful films weren’t so because they were uniquely Australian but because there was an element of universalism, it could take place anywhere or happen to anyone.

The Babadook, for example, is a genre film that crossed $10.3 million worldwide compared to its humble $2 million budget. The writer and director, cast, and film location were all Australian, but it was still a movie that played on the universal theme of fear.

Even though The Babadook had success internationally, in comparison it tanked in Australia, grossing only $258,000 and was only shown in 13 cinemas around the country. This highlights the need for more successful marketing campaigns as an incentive for Australians to support the local film industry. If we don’t know about local films or where to access them how can we possibly support the industry?

And finally, funding is crucial to the continuation of Australian film. Regardless of its perceived success in return of capital, it is important that art continues to be funded and supported just for its cultural importance in any community.